- Home

- Mary Stewart

The Crystal Cave Page 16

The Crystal Cave Read online

Page 16

The road north was an old one, paved, and the men who had built it had cleared the trees and scrub back on either side for a hundred paces, but with time and neglect the open verge had grown thick with whin and heather and young trees, so that now the forest seemed to crowd round you as you rode, and the way was dark.

Near the town we had seen one or two peasants carrying home fuel on their donkeys, and once one of Ambrosius' messengers spurred past us, with a stare, and what looked like a half-salute to me. But in the forest we met no one. It was the silent time between the thin birdsong of a March day and the hunting of the owls.

When we got among the big trees the rain had stopped, and the mist was thinning. Presently we came to a crossroads where a track — unpaved this time — crossed our own at right angles. The track was one used for hauling timber out of the forest, and also by the carts of charcoal burners, and, though rough and deeply rutted, it was clear and straight, and if you kept your horse to the edge, there was a gallop.

"Let's turn down here, Cadal."

"You know he said keep to the road."

"Yes, I know he did, but I don't see why. The forest's perfectly safe."

This was true. It was another thing Ambrosius had done; men were no longer afraid to ride abroad in Less Britain, within striking distance of the town. The country was constantly patrolled by his companies, alert and spoiling for something to do. Indeed, the main danger was (as I had once heard him admit) that his troops would over-train and grow stale, and look rather too hard for trouble. Meanwhile, the outlaws and disaffected men stayed away, and ordinary folk went about their business in peace. Even women could travel without much of an escort.

"Besides," I added, "does it matter what he said? He's not my master. He's only in charge of teaching me, nothing else. We can't possibly lose our way if we keep to the tracks, and if we don't get a canter now, it'll be too dark to press the horses when we get back to the fields. You're always complaining that I don't ride well enough. How can I, when we're always trotting along the road? Please, Cadal."

"Look, I'm not your master either. All right, then, but not far. And watch your pony; it'll be darker under the trees. Best let me go first."

I put a hand on his rein. "No. I'd like to ride ahead, and would you hold back a little, please? The thing is, I — I have so little solitude, and it's been something I'm used to. This was one of the reasons I had to come out this way." I added carefully: "It's not that I haven't been glad of your company, but one sometimes wants time to — well, to think things out. If you'll just give me fifty paces?"

He reined back immediately. Then he cleared his throat. "I told you I'm not your master. Go ahead. But go careful."

I turned Aster into the ride, and kicked him to a canter. He had not been out of his stable for three days, and in spite of the distance behind us he was eager. He laid his ears back, and picked up speed down the grass verge of the ride. Luckily the mist had almost gone, but here and there it smoked across the track saddle-high, and the horses plunged through it, fording it like water.

Cadal was holding well back; I could hear the thud of the mare's hoofs like a heavy echo of my pony's canter. The small rain had stopped, and the air was fresh and cool and resinous with the scent of pines. A woodcock flighted overhead with a sweet whispering call, and a soft tassel of spruce flicked a fistful of drops across my mouth and down inside the neck of my tunic. I shook my head and laughed, and the pony quickened his pace, scattering a pool of mist like spray. I crouched over his neck as the track narrowed, and branches whipped at us in earnest. It was darker; the sky thickened to nightfall between the boughs, and the forest rolled by in a dark cloud, wild with scent and silent but for Aster's scudding gallop and the easy pacing of the mare.

Cadal called me to stop. As I made no immediate response, the thudding of the mare's hoofs quickened, and drew closer. Aster's ears flicked, then flattened again, and he began to race. I drew him in. It was easy, as the going was heavy, and he was sweating. He slowed and then stood and waited quietly for Cadal to come up. The brown mare stopped. The only sound in the forest now was the breathing of the horses.

"Well," he said at length, "did you get what you wanted?"

"Yes, only you called too soon."

"We'll have to turn back if we're to be in time for supper. Goes well, that pony. You want to ride ahead on the way back?"

"If I may."

"I told you there's no question, you do as you like. I know you don't get out on your own, but you're young yet, and it's up to me to see you don't come to harm, that's all."

"What harm could I come to? I used to go everywhere alone at home."

"This isn't home. You don't know the country yet. You could lose yourself, or fall off your pony and lie in the forest with a broken leg —"

"It's not very likely, is it? You were told to watch me, why don't you admit it?"

"To look after you."

"It could come to the same thing. I've heard what they call you. 'The watchdog.'"

He grunted. "You don't need to dress it up. 'Merlin's black dog,' that's the way I heard it. Don't think I mind. I do as he says and no questions asked, but I'm sorry if it frets you."

"It doesn't — oh, it doesn't. I didn't mean it like that. It's all right, it's only... Cadal —"

"Yes?"

"Am I a hostage, after all?"

"That I couldn't say," said Cadal woodenly. "Come along, then, can you get by?"

Where our horses stood the way was narrow, the center of the ride having sunk into deep mud where water faintly reflected the night sky. Cadal reined his mare back into the thicket that edged the ride, while I forced Aster — who would not wet his feet unless compelled — past the mare. As the brown's big quarters pressed back into the tangle of oak and chestnut there was suddenly a crash just behind her, and a breaking of twigs, and some animal burst from the undergrowth almost under the mare's belly, and hurtled across the ride in front of my pony's nose.

Both animals reacted violently. The mare, with a snort of fear, plunged forward hard against the rein. At the same moment Aster shied wildly, throwing me half out of the saddle. Then the plunging mare crashed into his shoulder, and the pony staggered, whirled, lashed out, and threw me.

I missed the water by inches, landing heavily on the soft stuff at the edge of the ride, right up against a broken stump of pine which could have hurt me badly if I had been thrown on it. As it was I escaped with scratches and a minor bruise or two, and a wrenched ankle that, when I rolled over and tried to put it to the ground, stabbed me with pain momentarily so acute as to make the black woods swim.

Even before the mare had stopped circling Cadal was off her back, had flung the reins over a bough, and was stooping over me.

"Merlin — Master Merlin — are you hurt?"

I unclamped my teeth from my lip, and started gingerly with both hands to straighten my leg. "No, only my ankle, a bit."

"Let me see... No, hold still. By the dog, Ambrosius will have my skin for this."

"What was it?"

"A boar, I think. Too small for a deer, too big for a fox."

"I thought it was a boar, I smelled it. My pony?"

"Halfway home by now, I expect. Of course you had to let the rein go, didn't you?"

"I'm sorry. Is it broken?"

His hands had been moving over my ankle, prodding, feeling. "I don't think so... No, I'm sure it's not. You're all right otherwise? Here, come on, try if you can stand on it. The mare'll take us both, and I want to get back, if I can, before that pony of yours goes in with an empty saddle. I'll be for the lampreys, for sure, if Ambrosius sees him."

"It wasn't your fault. Is he so unjust?"

"He'll reckon it was, and he wouldn't be far wrong. Come on now, try it."

"No, give me a moment. And don't worry about Ambrosius, the pony hasn't gone home, he's stopped a little way up the ride. You'd better go and get him."

He was kneeling over me, and I could see him faintl

y against the sky. He turned his head to peer along the ride. Beside us the mare stood quietly, except for her restless ears and the white edge to her eye. There was silence except for an owl starting up, and far away on the edge of sound another, like its echo.

"It's pitch dark twenty feet away," said Cadal. "I can't see a thing. Did you hear him stop?"

"Yes." It was a lie, but this was neither the time nor the place for the truth. "Go and get him, quickly. On foot. He hasn't gone far."

I saw him stare down at me for a moment, then he got to his feet without a word and started off up the ride. As well as if it had been daylight, I could see his puzzled look. I was reminded, sharply, of Cerdic that day at King's Fort. I leaned back against the stump. I could feel my bruises, and my ankle ached, but for all that there came flooding through me, like a drink of warm wine, the feeling of excitement and release that came with the power. I knew now that I had had to come this way; that this was to be another of the hours when not darkness, nor distance, nor time meant anything. The owl floated silently above me, across the ride. The mare cocked her ears at it, watching without fear. There was the thin sound of bats somewhere above. I thought of the crystal cave, and Galapas' eyes when I told him of my vision. He had not been puzzled, not even surprised. It came to me to wonder, suddenly, how Belasius would look. And I knew he would not be surprised, either.

Hoofs sounded softly in the deep turf. I saw Aster first, approaching ghostly grey, then Cadal like a shadow at his head.

"He was there all right," he said, "and for a good reason. He's dead lame. Must have strained something."

"Well, at least he won't get home before we do."

"There'll be trouble over this night's work, that's for sure, whatever time we get home. Come on, then, I'll put you up on Rufa."

With a hand from him I got cautiously to my feet. When I tried to put weight on the left foot, it still hurt me quite a lot, but I knew from the feel of it that it was nothing but a wrench and would soon be better. Cadal threw me up on the mare's back, unhooked the reins from the bough, and gave them into my hand. Then he clicked his tongue to Aster, and led him slowly ahead.

"What are you doing?" I asked. "Surely she can carry us both?"

"There's no point. You can see how lame he is. He'll have to be led. If I take him in front he can make the pace. The mare'll stay behind him. — You all right up there?"

"Perfectly, thanks."

The grey pony was indeed dead lame. He walked slowly beside Cadal with drooping head, moving in front of me like a smoke-beacon in the dusk. The mare followed quietly. It would take, I reckoned, a couple of hours to get home, even without what lay ahead.

Here again was a kind of solitude, no sounds but the soft plodding of the horses' hoofs, the creak of leather, the occasional small noises of the forest round us. Cadal was invisible, nothing but a shadow beside the moving wraith of mist that was Aster. Perched on the big mare at a comfortable walk, I was alone with the darkness and the trees.

We had gone perhaps half a mile when, burning through the boughs of a huge oak to my right, I saw a white star, steady.

"Cadal, isn't there a shorter way back? I remember a track off to the south just near that oak tree. The mist's cleared right away, and the stars are out. Look, there's the Bear."

His voice came back from the darkness. "We'd best head for the road." But in a pace or two he stopped the pony at the mouth of the south-going track, and waited for the mare to come up.

"It looks good enough, doesn't it?" I asked. "It's straight, and a lot drier than this track we're on. All we have to do is keep the Bear at our backs, and in a mile or two we should be able to smell the sea. Don't you know your way about the forest?"

"Well enough. It's true this would be shorter, if we can see our way. Well..." I heard him loosen his short stabbing sword in its sheath. "Not that there's likely to be trouble, but best be prepared, so keep your voice down, will you, and have your knife ready. And let me tell you one thing, young Merlin, if anything should happen, then you'll ride for home and leave me to it. Got that?"

"Ambrosius' orders again?"

"You could say so."

"All right, if it makes you feel better, I promise I'll desert you at full speed. But there'll be no trouble."

He grunted. "Anyone would think you knew."

I laughed. "Oh, I do."

The starlight caught, momentarily, the whites of his eyes, and the quick gesture of his hand. Then he turned without speaking and led Aster into the track going south.

8

THOUGH THE PATH WAS WIDE ENOUGH to take two riders abreast, we went in single file, the brown mare adapting her long, comfortable stride to the pony's shorter and very lame step.

It was colder now; I pulled the folds of my cloak round me for warmth. The mist had vanished completely with the drop in temperature, the sky was clear, with some stars, and it was easier to see the way. Here the trees were huge; oaks mainly, the big ones massive and widely spaced, while between them saplings grew thickly and unchecked, and ivy twined with the bare strings of honeysuckle and thickets of thorn. Here and there pines showed fiercely black against the sky. I could hear the occasional patter as damp gathered and dripped from the leaves, and once the scream of some small creature dying under the claws of an owl. The air was full of the smell of damp and fungus and dead leaves and rich, rotting things.

Cadal trudged on in silence, his eyes on the path, which in places was tricky with fallen or rotting branches. Behind him, balancing on the big mare's saddle, I was still possessed by the same light, excited power. There was something ahead of us, to which I was being led, I knew, as surely as the merlin had led me to the cavern at King's Fort.

Rufa's ears pricked, and I heard her soft nostrils flicker. Her head went up. Cadal had not heard, and the grey pony, preoccupied with his lameness, gave no sign that he could smell the other horses. But even before Rufa, I had known they were there.

The path twisted and began to go gently downhill. To either side of us the trees had retreated a little, so that their branches no longer met overhead, and it was lighter. Now to each side of the path were banks, with outcrops of rock and broken ground where in summer there would be foxgloves and bracken, but where now only the dead and wiry brambles ran riot. Our horses' hoofs scraped and rang as they picked their way down the slope.

Suddenly Rufa, without checking her stride, threw up her head and let out a long whinny. Cadal, with an exclamation, stopped dead, and the mare pushed up beside him, head high, ears pricked towards the forest on our right. Cadal snatched at her bridle, pulled her head down, and shrouded her nostrils in the crook of his arm. Aster had lifted his head, too, but he made no sound.

"Horses," I said softly. "Can't you smell them?"

I heard Cadal mutter something that sounded like, "Smell anything, it seems you can, you must have a nose like a bitch fox," then, hurriedly starting to drag the mare off the track: "It's too late to go back, they'll have heard this bloody mare. We'd best pull off into the forest."

I stopped him. "There's no need. There's no trouble there, I'm certain of it. Let's go on."

"You talk fine and sure, but how can you know — ?"

"I do know. In any case, if they meant us harm, we'd have known of it by now. They've heard us coming long since, and they must know it's only two horses and one of them lame."

But he still hesitated, fingering his short sword. The prickles of excitement fretted my skin like burrs. I had seen where the mare's ears were pointing — at a big grove of pines, fifty paces ahead, and set back above the right of the path. They were black even against the blackness of the forest. Suddenly I could wait no longer. I said impatiently: "I'm going, anyway. You can follow or not, as you choose." I jerked Rufa's head up and away from him, and kicked her with my good foot, so that she plunged forward past the grey pony. I headed her straight up the bank and into the grove.

The horses were there. Through a gap in the thick roof of pines a cluste

r of stars burned, showing them clearly. There were only two, standing motionless, with their heads held low and their nostrils muffled against the breast of a slight figure heavily cloaked and hooded against the cold. The hood fell back as he turned to stare; the oval of his face showed pale in the gloom. There was no one else there.

For one startled moment I thought that the black horse nearest me was Ambrosius' big stallion, then as it pulled its head free of the cloak I saw the white blaze on its forehead, and knew in a flash like a falling star why I had been led here.

Behind me, with a scramble and a startled curse, Cadal pulled Aster into the grove. I saw the grey gleam of his sword as he lifted it. "Who's that?"

I said quietly, without turning: "Put it up. It's Belasius. At least that's his horse. Another with it, and the boy. That's all."

He advanced. His sword was already sliding back into its housing. "By the dog, you're right, I'd know that white flash anywhere. Hey, Ulfin, well met. Where's your master?"

Even at six paces I heard the boy gasp with relief. "Oh, it's you, Cadal... My lord Merlin... I heard your horse whinny — I wondered — Nobody comes this way."

I moved the mare forward, and looked down. His face was a pale blur upturned, the eyes enormous. He was still afraid.

"It seems Belasius does," I said. "Why?"

"He — he tells me nothing, my lord."

Cadal said roundly: "Don't give us that. There's not much you don't know about him, you're never more than arm's length from him, day or night, everybody knows that. Come on, out with it. Where's your master?"

"I — he won't be long."

"We can't wait for him," said Cadal. "We want a horse. Go and tell him we're here, and my lord Merlin's hurt, and the pony's lame, and we've got to get home quickly... Well? Why don't you go? For pity's sake, what's the matter with you?"

"I can't. He said I must not. He forbade me to move from here."

Madam, Will You Talk?

Madam, Will You Talk? Legacy: Arthurian Saga 1-4

Legacy: Arthurian Saga 1-4 The Hollow Hills

The Hollow Hills The Wicked Day

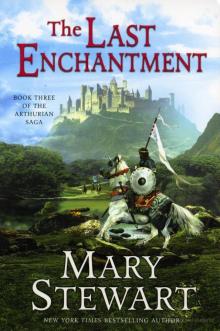

The Wicked Day The Last Enchantment

The Last Enchantment Wildfire at Midnight

Wildfire at Midnight The Crystal Cave

The Crystal Cave Thunder on the Right

Thunder on the Right Airs Above the Ground

Airs Above the Ground The Ivy Tree

The Ivy Tree Rose Cottage

Rose Cottage The Gabriel Hounds

The Gabriel Hounds Legacy: Arthurian Saga

Legacy: Arthurian Saga The Wind Off the Small Isles

The Wind Off the Small Isles The Moonspinners

The Moonspinners My Brother Michael

My Brother Michael The Prince and the Pilgrim

The Prince and the Pilgrim A Wlk in Wolf Wood

A Wlk in Wolf Wood Touch Not the Cat

Touch Not the Cat The Little Broomstick

The Little Broomstick Thornyhold

Thornyhold This Rough Magic

This Rough Magic The Stormy Petrel

The Stormy Petrel Wicked Day

Wicked Day Hollow Hills

Hollow Hills WILDFIRE

WILDFIRE Stormy Petrel

Stormy Petrel Legacy

Legacy Crystal Cave

Crystal Cave Last Enchantment

Last Enchantment