- Home

- Mary Stewart

Thunder on the Right Page 5

Thunder on the Right Read online

Page 5

‘Yes, indeed. She wrote herself to ask me to come. She recommended a hotel in Gavarnie, and said she would see if I could be housed for a little while here, at the convent.’

‘Then surely,’ said Sister Louisa, with another of her bright glances, ‘surely it’s more strange still that she didn’t speak of you to anyone?’

‘I thought so at first,’ said Jennifer, ‘but, of course, if she was delirious with fever, she would hardly remember—’

‘Well, yes, of course. But there were many times when she was lucid, too. That’s why it seems so odd—’

Jennifer sat back abruptly on her heels and stared at Sister Louisa.

‘You mean – she wasn’t feverish all the time?’

‘Of course not. You know how these things go; there is delirium, followed often by a period when the patient’s mind is quite clear – very weak, you understand, but quite sensible. She did have times like that, so I believe.’

‘But,’ said Jennifer, ‘Doña Francisca gave me to understand that Gillian – my cousin – was delirious all the time, and had no chance to remember me!’

Sister Louisa’s shoulders lifted in a remarkably unmonastic shrug. ‘As to that, I can’t tell you any more, child. I didn’t see your cousin myself, but I had certainly understood from Celeste—’

‘Celeste?’

‘One of the orphans – the eldest of them, a sweet child. She and Doña Francisca nursed your cousin.’

‘Doña Francisca did that?’

‘Indeed yes. She’s skilled at it. It was she who took her in, and she insisted on looking after her herself with Celeste to help her. We’re a tiny community, you know, and though Doña Francisca may have a temper and a high-nosed Spanish way with her’ – she grinned suddenly – ‘she’s a good doctor in sickness. I can speak for that myself: I get rheumatism every winter, and she’s very good to me.’

‘And Celeste told you that my cousin had these periods of sanity?’

‘I don’t know whether she said so for sure, but that’s what I’d understood. In fact, that’s why I’m so busy here planting these things – you know what they are, child?’

‘No, what?’

‘Gentians. They’re bonny flowers. In the spring the grass on the grave will be blue, bluer even than those morning glories.’

Jennifer stared at her. ‘But—’

‘Oh, yes, there are gentians out now, on the mountains, I know. Look, there’s some here now in this bowl. But the ones I’m setting are the spring ones. I brought them in myself so that she’d have gentians for the spring. She loved the colour, you know. Celeste told me that. That’s what made me understand your cousin had been able to talk sense for a bit; she told Celeste these were her favourite flowers. She’d hardly say that in delirium, would she?’

‘Hardly. But—’

‘Celeste used to gather them for her, and when she died, I planned to plant them on her grave. It’s a small service, but one I like to do for them …’ She made a little gesture towards two other flower-covered mounds. ‘Sister Thérèse loved pansies, you see, and old Sister Marianne always said the prettiest flower of them all was the mountain daisy. And so here are gentians for your cousin …’

‘I – I see. It’s very sweet of you.’ But something – some shaken and breathless undertone in Jennifer’s voice – made the old nun cock an eye at her again.

‘What’s the matter, child?’

Jennifer did not reply for a moment. She sat looking down at her hands, gripped tightly together in her lap, while her grief-stupefied mind struggled to assess a new and sufficiently startling idea.

Sister Louisa put down her trowel with a tiny slap. ‘Something’s up. What is it?’

Jennifer looked up then, thrusting back the soft hair from her forehead as if by that act she could comb away the tangles of her confusion. She met the anxious old eyes levelly.

‘Sister Louisa, my cousin was colour-blind.’

The old woman gave her a puzzled glance, then reached half-automatically for her trowel again. She picked up another plant and began to set it in its place. ‘Well?’

‘You understand what that means?’

‘Well, of course. When I was a girl I had a friend whose brother suffered the same way. They might never have known it, but he went to work on the railway, and they soon found out and dismissed him. It was the signals, you understand – the red and green lights. He couldn’t read them.’ She thrust the earth down round the gentian’s roots. ‘A misfortune, child, but like all misfortunes, it concealed the hand of God. He took a job as a waiter instead, and now he has his own restaurant in Menton, and six children, and his wife is dead. Which,’ added Sister Louisa, slapping the earth down smartly with the trowel, ‘you would also count as a blessing, if you had known his wife. God rest her soul.’

‘Quite,’ said Jennifer, uncertain of the response to this gambit.

Sister Louisa passed it with a momentary twinkle. ‘But – your cousin, you said? I always understood that it was a thing men suffered from, not women, mademoiselle. The doctor told us that, I remember.’

‘Yes,’ said Jennifer. ‘It’s quite true that it’s usually men who are colour-blind, and the commonest kind of blindness, at that, is the kind your friend’s brother had, which confuses red and green. But Gillian – my cousin – was not only colour-blind, she suffered from a very rare variation of it, tritanopia.’

Sister Louisa put down her trowel again, and looked at her with deepening bewilderment.

‘What?’

Jennifer had used what she imagined must be the French equivalent for the word – la tritanopie. She plunged on this again. ‘Tritanopia. It’s blue-and-yellow blindness.’

Sister Louisa’s gaze moved to the bowl of gentians, blazing blue against the grass. Then it returned, wonderingly, to Jennifer. ‘You’re telling me that your cousin, that Madame Lamartine—?’

Jennifer nodded. ‘She couldn’t distinguish blue from yellow at all: as far as one knows she saw them both as varying tones of grey. In other words,’ she finished, ‘she wouldn’t have known a gentian if she saw one!’

The old nun looked down at the plant she had just set on the side of the mound. ‘I must have been mistaken,’ she said humbly. ‘But when I got them for her I was so sure—’

Jennifer leaned forward swiftly and touched her hand. Her face was taut.

‘No, Sister! How could you be mistaken about such a simple thing – you and Celeste as well? You told me that Celeste often picked them for her?’

‘Yes, but—’

‘Who gathered these?’ Jennifer indicated the bowl on the grave.

‘Celeste.’

‘And Celeste did tell you, in so many words, that Madame Lamartine had liked the gentians, and said they were her favourite flowers?’

‘Oh, yes, she said that. But, my child’ – the old nun’s eyes were still bewildered – ‘I don’t understand. Why should your cousin pretend—?’ She broke off, and shrugged her shoulders. ‘But after all, it’s no great matter. This – these flowers I plant – it is only a gesture, that’s all, a gesture for the living. Daisies, pansies, gentians … they are all one to the dead.’ She picked up her trowel, and returned once more to her task. Her eyes lifted briefly to Jennifer’s strained face. She added, gently: ‘What’s the matter, child? It is nothing, after all. A mistake—’

‘But it can’t be a mistake!’ cried Jennifer. ‘It’s such nonsense, that’s what worries me! As you said, why should she pretend, and over such a silly little thing, too, when all the time—’ She broke off and sat biting her underlip. Her fingers tore nervously at the short grass. ‘At any rate, it’s – queer,’ she finished, and, suddenly, for some reason, found herself remembering Doña Francisca’s hooded and obsidian gaze. A tiny shiver touched her out of nowhere. ‘Queer,’ she added, half to herself, ‘another thing that’s queer …’

Sister Louisa rammed the soil round another plant with thick, capable fingers, and then wiped her hands on the gras

s. She said, sturdily practical once more: ‘I think, my child, that we’re making a mystery out of nothing. And it isn’t even “queer”; if you think of it, your cousin was surely only being polite. If Celeste gathered flowers for her and brought them, of course she would say she liked them: she might even, to please the child, say they were her favourite flowers. You mark my words, it’s as simple as that.’

‘Oh, yes,’ said Jennifer. ‘Oh, yes. Only—’

‘Only?’

‘If she was sufficiently mistress of herself to think of courtesies like that, she was able also to send a message to me,’ said Jennifer flatly. ‘And that, after all, was rather more important.’

‘Yes, yes, of course. You are right. It is odd that she didn’t do that.’

‘If she did not,’ said Jennifer.

Across the charged little silence she met the startled gaze of the old nun squarely. She said, measuring her words: ‘Doña Francisca certainly gave me to understand that my cousin said nothing about me and sent no message. But then Doña Francisca also gave me to understand that my cousin had never come out of her delirium. You say the last statement isn’t true. Perhaps the first isn’t either.’

‘I – my child—’ The old nun faltered and stopped. The stubby hands which she twisted together were beginning to shake. It was obvious that the pleasures of slightly malicious gossip were one thing, but this direct accusation quite another. Bewilderment and distress clouded the old eyes. ‘All this talk – I don’t understand.’

‘No more do I,’ said Jennifer, and was momentarily surprised at the hardness of her own voice. ‘This girl, Celeste: is she likely to be lying?’

Inevitably, the emphasis was there, laying itself faintly on the pronoun, conjuring up on the moment the image of the other ‘she’. It was as if the long shadow of the Spanish woman lay coldly between them across the turf.

The old nun’s hands were frankly unsteady now, so too was her mouth. ‘Celeste? Oh, yes; oh, yes. She is a dear, good girl, a dear, good girl. She would never lie …’ Again the emphasis. The shadow stirred. ‘And why should she? To say that Madame Lamartine liked the gentians – it’s so unimportant, that, so trivial—’

‘Exactly.’ Jennifer looked away from the old woman’s patent distress. She sat back on her heels, her eyes on the lovely tracery of the gate that barred back the spendthrift green-and-gold of the apricot trees, and spoke softly. ‘One does not trouble to lie, Sister, about things that don’t matter.’

The old nun said nothing.

‘Look at it,’ said Jennifer, ‘look at it both ways. If she spoke about the gentians out of mere politeness – felt, in fact, well enough to talk about trivialities, why did she send no message to me? If, on the other hand, her liking for the flowers was genuine …’

Sister Louisa sat quite still. ‘Well, child?’

‘Then she had no message to send because,’ said Jennifer, ‘she had never heard of me. She spoke no English because she didn’t know any. Don’t you see?’

She was kneeling upright now, facing the old nun, her hands pressed down hard on her thighs. The knuckles showed bone-white.

‘Don’t you see what it means?’ she repeated, almost in a whisper. ‘It means that it wasn’t my cousin Gillian!’

Across the vibrant blue of the gentians the two stared at one another.

‘In either case,’ said Jenny, ‘I don’t believe the woman who died could have been Gillian!’

Deep in the convent buildings, imperatively, a bell rang.

6

Les Présages

It was as if the sharp sound of the bell recalled them both from some confused borderland of suspicion to the sane realities of the sunlit afternoon. Sister Louisa started, with a little exclamation, and began hastily to gather her tools together. Her hands still trembled slightly, and her movements were confused and age-betraying, but with the ringing of the bell she seemed to recollect, if not the complete serenity, at least some of the dignity and poise of her vocation.

She said, with a very creditable assumption of calm reproach: ‘You are distressed, my child; you can’t know what you are saying. It isn’t possible that such a mistake—’ She broke off, swallowed, and said bravely: ‘There’d – why there’d be no earthly reason why Doña – why anyone should lie to you.’

Jennifer said nothing. She, too, had been recalled to herself, to a sharp realization of her folly in speaking like this to one of the community to which Doña Francisca – in whatever capacity – belonged. And the force of Sister Louisa’s last statement could by no means be denied.

‘Besides,’ said Sister Louisa, almost querulously, ‘there were papers. She had papers.’

Jennifer looked up quickly. ‘Had she?’

‘Yes. You must see them. They’ll show you – but we won’t speak about it any more,’ said the old nun firmly, and groped uncertainly in the grass at the foot of the grave. ‘Now where did I put my little fork?’

‘It’s here, under the roses.’

‘Thank you, my child. That’s the lot, I think. Now I must go. That’s the bell for the children’s service.’ She began, somewhat creakily, to rise. Jennifer got to her feet, and lent her a hand. ‘Thank you, my child,’ said Sister Louisa again, and peered sideways up at her, adding with a quiver still in her voice: ‘And as to what we’ve been saying – don’t think of it again. It was wrong of me to listen, but you were in such distress – believe me, I understand how grieved and shocked you are. It came too suddenly, and you were perhaps not told the news’ – she paused – ‘as you should have been. You’ll feel different tomorrow when you’ve had some sleep. All these – ideas; they’ll sort themselves out and disappear in the morning.’

‘Yes.’

Sister Louisa patted her on the arm, her confidence palpably increasing. ‘You’re upset,’ she said, ‘and unhappy, and you can’t make yourself accept the fact that your cousin’s dead. But you will – you really will – feel better tomorrow.’

‘Joy,’ said Jennifer in a tight little voice, ‘cometh in the morning?’

The old nun blinked at her, disconcerted. Then Jennifer, with a swift movement, covered the old woman’s hand with her own and pressed it. ‘I’m sorry,’ she said, and smiled with an effort. ‘You’re quite right, Sister. I was upset. I was being silly. Of course all these things can be naturally explained. Tomorrow, perhaps—’

Sister Louisa seized on the word as if it were a magic formula. ‘Tomorrow. Yes, tomorrow. You go back to your hotel now, child, and see you get a good meal tonight – with wine, mind you, to make you sleep – and have a good night’s rest. Then if you’re still worried, you come and see us again. We’ve nothing to hide!’ She managed a ghost of her old chortle at the absurdity of this idea, and Jennifer smiled with her. ‘It’ll be quite easy to sort out all this nonsense,’ said the old nun. ‘Doña Francisca and Celeste will be only too glad to tell you everything they can.’

The smile was wiped from Jenny’s lips. She said quickly: ‘You won’t tell them what I’ve been saying? I – I wasn’t myself. I said some very silly things: please won’t you forget them, and say no more?’

‘All forgotten,’ said Sister Louisa stoutly. ‘Don’t worry, child, I’ll not tell.’ She cast a shrewd and still bothered eye at Jennifer. ‘If you’ve any more worries, you know, you ought to take them where they belong – to the Reverend Mother. You ought to see her anyway.’

‘Of course,’ said Jennifer. ‘Of course that’s what I should do. I’ll certainly go and talk to her.’

‘You do. Everything’ll be cleared up in no time. And now I must hurry, or I shall be late for chapel.’ She twinkled at Jennifer in almost her old manner. ‘You’d think I’d be a very holy woman, wouldn’t you, with the amount of kneeling I do, instead of an earthy old sinner who thinks about apples and roses a good deal more than she ought? But you’ll forget anything I said that I shouldn’t have said?’

Jennifer smiled and echoed: ‘All forgotten.’

&

nbsp; ‘Bless you, child. Can you find your own way out?’

‘I think so, thank you.’

‘Then I must leave you. Au revoir, mon enfant.’

‘Au revoir, ma sœur.’

The old Sister vanished through the wrought-iron gateway, and Jennifer was left alone in the graveyard.

But only for a moment, for, as she paused irresolute by the gentian-covered grave, the door in the outer wall opened without a sound, and a girl slipped through. She closed the door quietly behind her, then, as she turned, she saw Jennifer and stopped dead, her lips parted, her breast rising and falling as if she had been running. She was young, dark, and very lovely; even the faded blue cotton of her orphan’s garb could not deny the eager grace of her body. Her hair hung loosely over her shoulders, as if the wind of her running had tossed and ruffled it out, and her cheeks were flushed. Her hands were full of flowers.

She hesitated for a moment, looking at Jennifer, then she crossed the grass swiftly towards her, and knelt down by the new grave. She pulled the fading gentians out of the bowl, and began, rather hurriedly, to arrange the fresh ones in their place.

‘Are you Celeste?’

The girl shot her a shy upward look and nodded. Jennifer said: ‘I am Madame Lamartine’s cousin. I came to visit her today, and was told of her death. Sister Louisa tells me that you helped to nurse her. I’m very grateful to you.’

Celeste had sat back on her heels and was regarding Jennifer with wide eyes. ‘Her cousin?’ Her look was both puzzled and distressed. ‘I – I am sorry, madame. It must have been a great shock to find – to hear – I am so very sorry, madame …’

‘Yes,’ said Jennifer, ‘it was.’ She was watching the girl, but the beautiful eyes held nothing but compassion, and a growing bewilderment. ‘I did not know she had a cousin,’ said Celeste. ‘If we had known, madame, that there were relatives—’

‘You would no doubt have informed them of her illness, or at least of her death?’ said Jennifer gently.

‘But of course!’ cried Celeste. With a quick gesture she pushed the hair back from her face, and stared up at Jennifer. ‘Is it not strange, madame, that she should not have told us?’

Madam, Will You Talk?

Madam, Will You Talk? Legacy: Arthurian Saga 1-4

Legacy: Arthurian Saga 1-4 The Hollow Hills

The Hollow Hills The Wicked Day

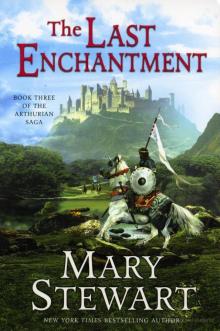

The Wicked Day The Last Enchantment

The Last Enchantment Wildfire at Midnight

Wildfire at Midnight The Crystal Cave

The Crystal Cave Thunder on the Right

Thunder on the Right Airs Above the Ground

Airs Above the Ground The Ivy Tree

The Ivy Tree Rose Cottage

Rose Cottage The Gabriel Hounds

The Gabriel Hounds Legacy: Arthurian Saga

Legacy: Arthurian Saga The Wind Off the Small Isles

The Wind Off the Small Isles The Moonspinners

The Moonspinners My Brother Michael

My Brother Michael The Prince and the Pilgrim

The Prince and the Pilgrim A Wlk in Wolf Wood

A Wlk in Wolf Wood Touch Not the Cat

Touch Not the Cat The Little Broomstick

The Little Broomstick Thornyhold

Thornyhold This Rough Magic

This Rough Magic The Stormy Petrel

The Stormy Petrel Wicked Day

Wicked Day Hollow Hills

Hollow Hills WILDFIRE

WILDFIRE Stormy Petrel

Stormy Petrel Legacy

Legacy Crystal Cave

Crystal Cave Last Enchantment

Last Enchantment